Inspired by a

Mastodon

post by Fran oise Conil,

who investigated the current popularity of build backends used in

pyproject.toml files, I wanted to investigate how the popularity of build

backends used in

pyproject.toml files evolved over the years since the

introduction of

PEP-0517 in 2015.

Getting the data

Tom Forbes provides a huge

dataset that contains information

about every file within every release uploaded to

PyPI. To

get the current dataset, we can use:

curl -L --remote-name-all $(curl -L "https://github.com/pypi-data/data/raw/main/links/dataset.txt")

This will download approximately 30GB of parquet files, providing detailed

information about each file included in a PyPI upload, including:

- project name, version and release date

- file path, size and line count

- hash of the file

The dataset does not contain the actual files themselves though, more on that

in a moment.

Querying the dataset using duckdb

We can now use

duckdb to query the parquet files directly. Let s look into

the schema first:

describe select * from '*.parquet';

column_name column_type null

varchar varchar varchar

project_name VARCHAR YES

project_version VARCHAR YES

project_release VARCHAR YES

uploaded_on TIMESTAMP YES

path VARCHAR YES

archive_path VARCHAR YES

size UBIGINT YES

hash BLOB YES

skip_reason VARCHAR YES

lines UBIGINT YES

repository UINTEGER YES

11 rows 6 columns

From all files mentioned in the dataset, we only care about

pyproject.toml

files that are in the project s root directory. Since we ll still have to

download the actual files, we need to get the

path and the

repository to

construct the corresponding URL to the mirror that contains all files in a

bunch of huge git repositories. Some files are not available on the mirrors; to

skip these, we only take files where the

skip_reason is empty. We also care

about the timestamp of the upload (

uploaded_on) and the

hash to avoid

processing identical files twice:

select

path,

hash,

uploaded_on,

repository

from '*.parquet'

where

skip_reason == '' and

lower(string_split(path, '/')[-1]) == 'pyproject.toml' and

len(string_split(path, '/')) == 5

order by uploaded_on desc

This query runs for a few minutes on my laptop and returns ~1.2M rows.

Getting the actual files

Using the

repository and

path, we can now construct an URL from which we

can fetch the actual file for further processing:

url = f"https://raw.githubusercontent.com/pypi-data/pypi-mirror- repository /code/ path "

We can download the individual

pyproject.toml files and parse them to read

the

build-backend into a dictionary mapping the file-

hash to the build

backend. Downloads on

GitHub are rate-limited, so downloading 1.2M files

will take a couple of days. By skipping files with a hash we ve already

processed, we can avoid downloading the same file more than once, cutting the

required downloads by circa 50%.

Results

Assuming the data is complete and my analysis is sound, these are the findings:

There is a surprising amount of build backends in use, but the overall amount

of uploads per build backend decreases quickly, with a long tail of single

uploads:

>>> results.backend.value_counts()

backend

setuptools 701550

poetry 380830

hatchling 56917

flit 36223

pdm 11437

maturin 9796

jupyter 1707

mesonpy 625

scikit 556

...

postry 1

tree 1

setuptoos 1

neuron 1

avalon 1

maturimaturinn 1

jsonpath 1

ha 1

pyo3 1

Name: count, Length: 73, dtype: int64

We pick only the top 4 build backends, and group the remaining ones (including

PDM and

Maturin) into other so they are accounted for as well.

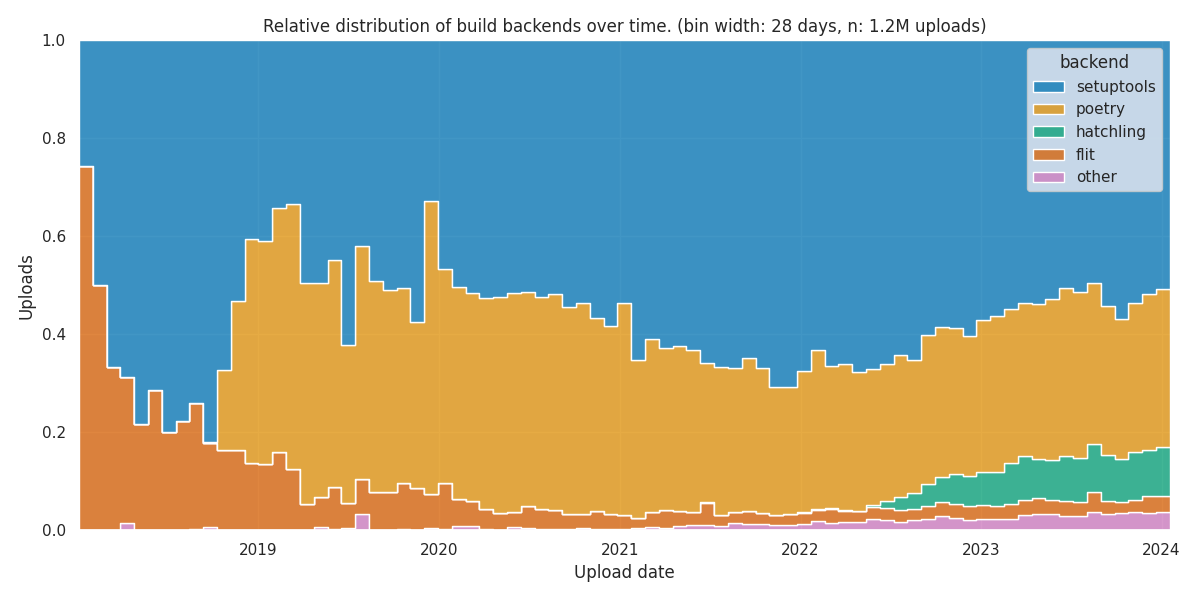

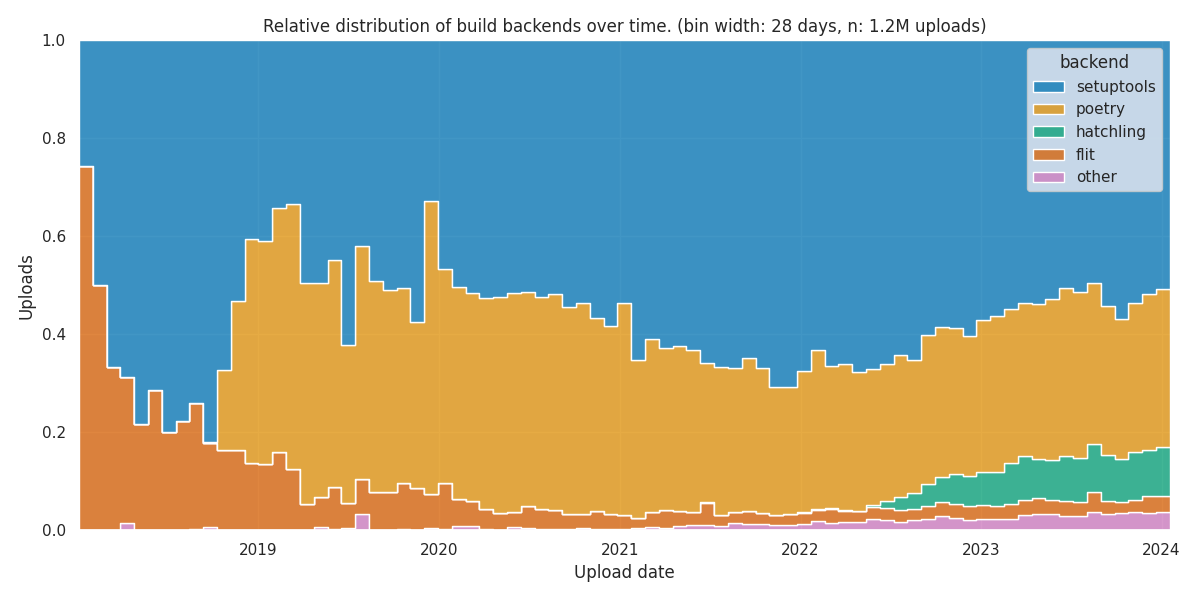

The following plot shows the relative distribution of build backends over time.

Each bin represents a time span of 28 days. I chose 28 days to reduce visual

clutter. Within each bin, the height of the bars corresponds to the relative

proportion of uploads during that time interval:

Looking at the right side of the plot, we see the current distribution. It

confirms Fran oise s findings about the current popularity of build

backends:

- Setuptools: ~50%

- Poetry: ~33%

- Hatch: ~10%

- Flit: ~3%

- Other: ~4%

Between 2018 and 2020 the graph exhibits significant fluctuations, due to the

relatively low amount uploads utizing

pyproject.toml files. During that early

period,

Flit started as the most popular build backend, but was eventually

displaced by

Setuptools and

Poetry.

Between 2020 and 2020, the overall usage of

pyproject.toml files increased

significantly. By the end of 2022, the share of

Setuptools peaked at 70%.

After 2020, other build backends experienced a gradual rise in popularity.

Amongh these,

Hatch emerged as a notable contender, steadily gaining

traction and ultimately stabilizing at 10%.

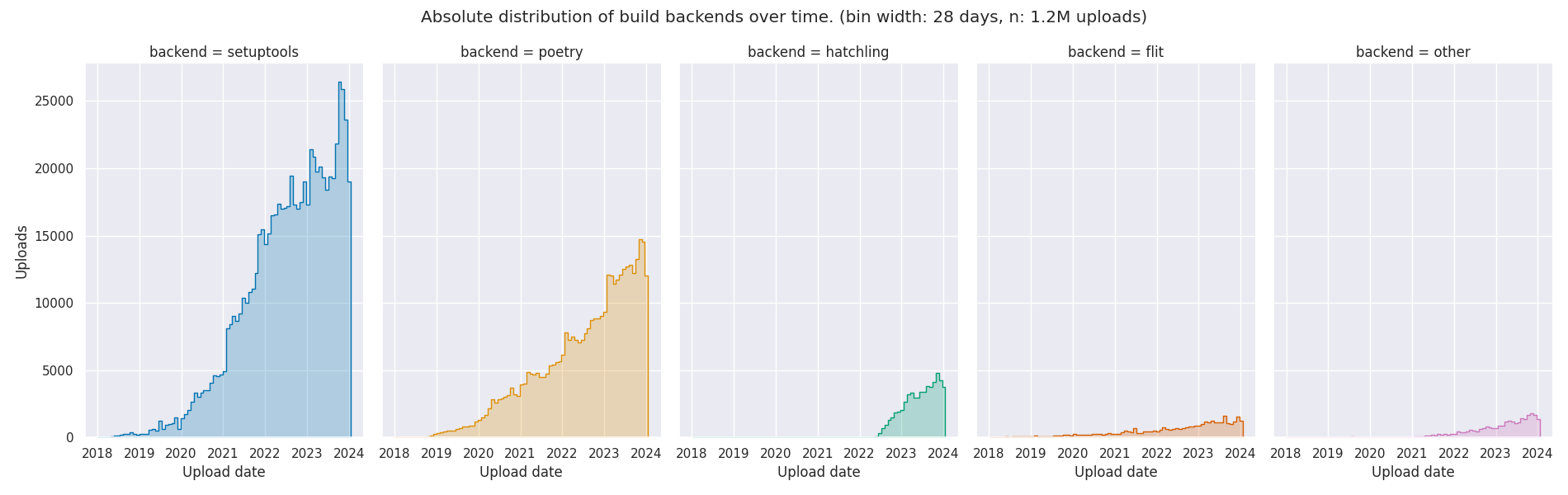

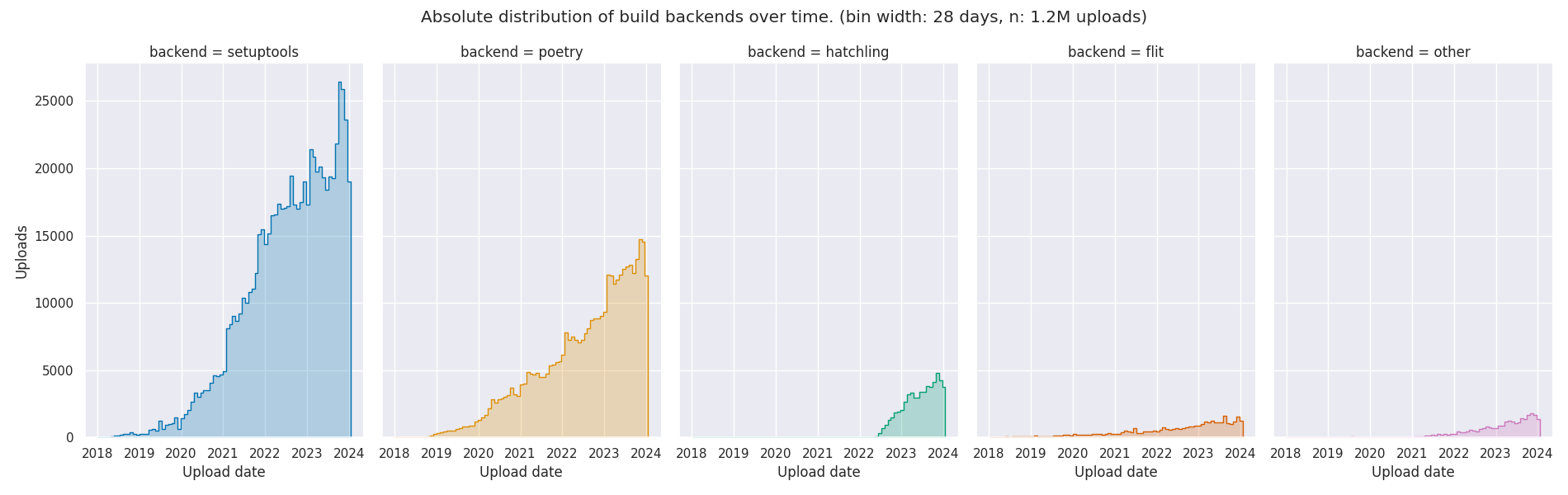

We can also look into the absolute distribution of build backends over time:

The plot shows that Setuptools has the strongest growth trajectory, surpassing

all other build backends. Poetry and Hatch are growing at a comparable rate,

but since Hatch started roughly 4 years after Poetry, it s lagging behind in

popularity. Despite not being among the most widely used backends anymore, Flit

maintains a steady and consistent growth pattern, indicating its enduring

relevance in the Python packaging landscape.

The script for downloading and analyzing the data can be found in my

GitHub

repository. It contains the results of the duckb query (so you

don t have to download the full dataset) and the pickled dictionary, mapping

the file hashes to the build backends, saving you days for downloading and

analyzing the

pyproject.toml files yourself.

This article is cross-posting from grow-your-ideas. This is just an idea.

salsa.debian.org

This article is cross-posting from grow-your-ideas. This is just an idea.

salsa.debian.org

ref. https://qa.debian.org/dose/debcheck/unstable_main/index.html

ref. https://qa.debian.org/dose/debcheck/unstable_main/index.html

ref. https://qa.debian.org/dose/debcheck/unstable_main/index.html

ref. https://qa.debian.org/dose/debcheck/unstable_main/index.html

The Amazon Kids parental controls are extremely insufficient, and I strongly advise against getting any of the Amazon Kids series.

The initial permise (and some older reviews) look okay: you can set some time limits, and you can disable anything that requires buying.

With the hardware you get one year of the Amazon Kids+ subscription, which includes a lot of interesting content such as books and audio,

but also some apps. This seemed attractive: some learning apps, some decent games.

Sometimes there seems to be a special Amazon Kids+ edition , supposedly one that has advertisements reduced/removed and no purchasing.

However, there are so many things just wrong in Amazon Kids:

The Amazon Kids parental controls are extremely insufficient, and I strongly advise against getting any of the Amazon Kids series.

The initial permise (and some older reviews) look okay: you can set some time limits, and you can disable anything that requires buying.

With the hardware you get one year of the Amazon Kids+ subscription, which includes a lot of interesting content such as books and audio,

but also some apps. This seemed attractive: some learning apps, some decent games.

Sometimes there seems to be a special Amazon Kids+ edition , supposedly one that has advertisements reduced/removed and no purchasing.

However, there are so many things just wrong in Amazon Kids:

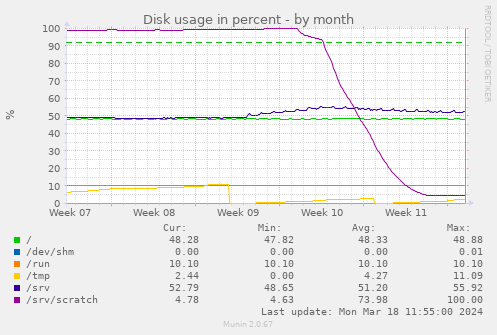

Debian is running a "

Debian is running a " The initial dip from 100% to 95% is my first "what happens if we block repos

> 500 MB" attempt. Over the week after that, the git filter clones reduce the

overall disk consumption from almost 300 GB to 15 GB, a 1/20. Some

repos shrank from GBs to below a MB.

Perhaps I should make all my git clones use one of the filters.

The initial dip from 100% to 95% is my first "what happens if we block repos

> 500 MB" attempt. Over the week after that, the git filter clones reduce the

overall disk consumption from almost 300 GB to 15 GB, a 1/20. Some

repos shrank from GBs to below a MB.

Perhaps I should make all my git clones use one of the filters.

Closing arguments in the trial between various people and

Closing arguments in the trial between various people and

Like each month, have a look at the work funded by

Like each month, have a look at the work funded by  I like using one machine and setup for everything, from serious development work to hobby projects to managing my finances. This is very convenient, as often the lines between these are blurred. But it is also scary if I think of the large number of people who I have to trust to not want to extract all my personal data. Whenever I run a

I like using one machine and setup for everything, from serious development work to hobby projects to managing my finances. This is very convenient, as often the lines between these are blurred. But it is also scary if I think of the large number of people who I have to trust to not want to extract all my personal data. Whenever I run a

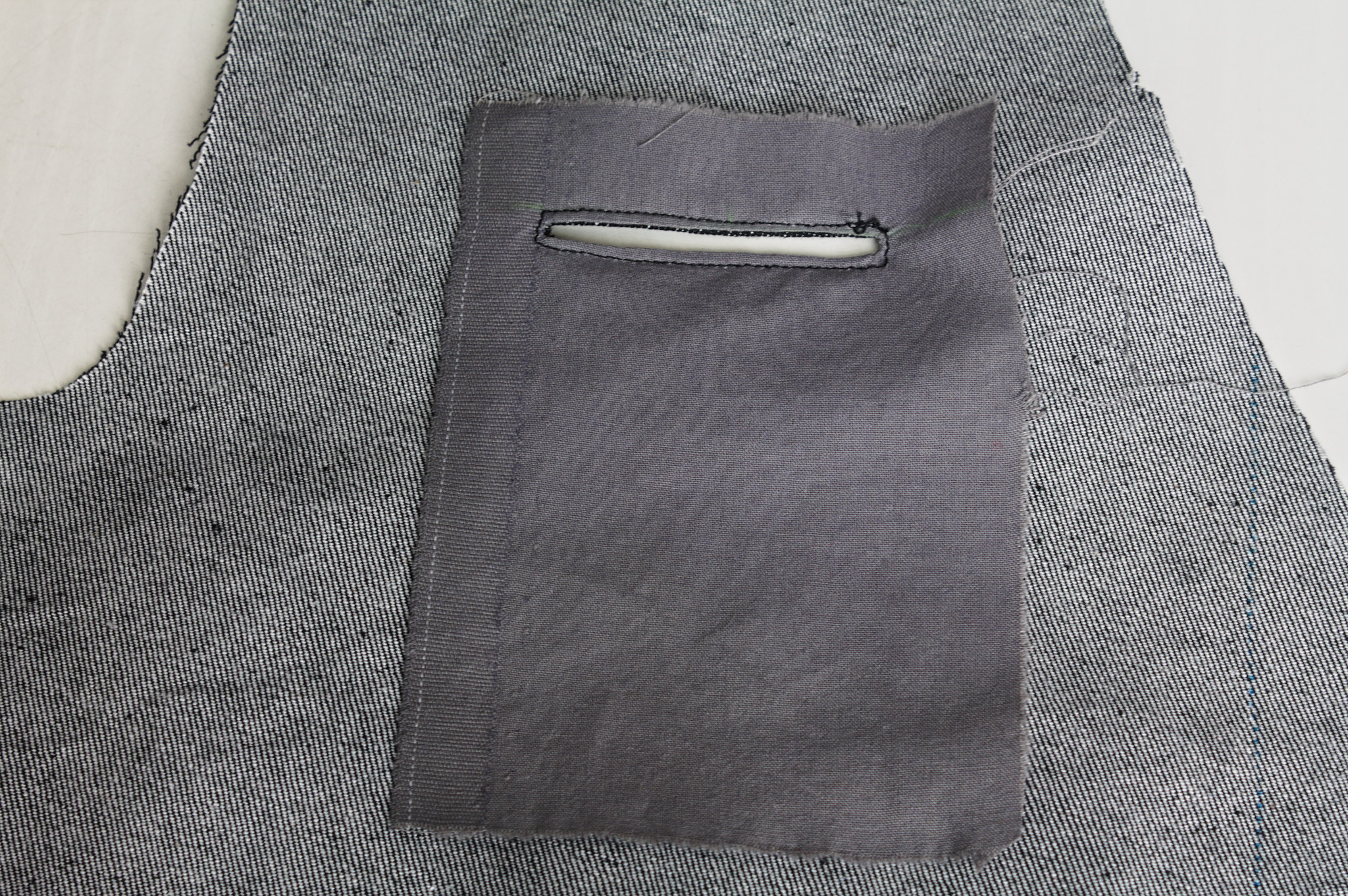

I had finished sewing my jeans, I had a scant 50 cm of elastic denim

left.

Unrelated to that, I had just finished drafting a vest with Valentina,

after

I had finished sewing my jeans, I had a scant 50 cm of elastic denim

left.

Unrelated to that, I had just finished drafting a vest with Valentina,

after

The other thing that wasn t exactly as expected is the back: the pattern

splits the bottom part of the back to give it sufficient spring over

the hips . The book is probably published in 1892, but I had already

found when drafting the foundation skirt that its idea of hips

includes a bit of structure. The enough steel to carry a book or a cup

of tea kind of structure. I should have expected a lot of spring, and

indeed that s what I got.

To fit the bottom part of the back on the limited amount of fabric I had

to piece it, and I suspect that the flat felled seam in the center is

helping it sticking out; I don t think it s exactly bad, but it is

a peculiar look.

Also, I had to cut the back on the fold, rather than having a seam in

the middle and the grain on a different angle.

Anyway, my next waistcoat project is going to have a linen-cotton lining

and silk fashion fabric, and I d say that the pattern is good enough

that I can do a few small fixes and cut it directly in the lining, using

it as a second mockup.

As for the wrinkles, there is quite a bit, but it looks something that

will be solved by a bit of lightweight boning in the side seams and in

the front; it will be seen in the second mockup and the finished

waistcoat.

As for this one, it s definitely going to get some wear as is, in casual

contexts. Except. Well, it s a denim waistcoat, right? With a very

different cut from the get a denim jacket and rip out the sleeves , but

still a denim waistcoat, right? The kind that you cover in patches,

right?

The other thing that wasn t exactly as expected is the back: the pattern

splits the bottom part of the back to give it sufficient spring over

the hips . The book is probably published in 1892, but I had already

found when drafting the foundation skirt that its idea of hips

includes a bit of structure. The enough steel to carry a book or a cup

of tea kind of structure. I should have expected a lot of spring, and

indeed that s what I got.

To fit the bottom part of the back on the limited amount of fabric I had

to piece it, and I suspect that the flat felled seam in the center is

helping it sticking out; I don t think it s exactly bad, but it is

a peculiar look.

Also, I had to cut the back on the fold, rather than having a seam in

the middle and the grain on a different angle.

Anyway, my next waistcoat project is going to have a linen-cotton lining

and silk fashion fabric, and I d say that the pattern is good enough

that I can do a few small fixes and cut it directly in the lining, using

it as a second mockup.

As for the wrinkles, there is quite a bit, but it looks something that

will be solved by a bit of lightweight boning in the side seams and in

the front; it will be seen in the second mockup and the finished

waistcoat.

As for this one, it s definitely going to get some wear as is, in casual

contexts. Except. Well, it s a denim waistcoat, right? With a very

different cut from the get a denim jacket and rip out the sleeves , but

still a denim waistcoat, right? The kind that you cover in patches,

right?

Two months into my

Two months into my  We are thrilled to share that

We are thrilled to share that  In light of the recent

In light of the recent

Insert obligatory "not THAT data" comment here

Insert obligatory "not THAT data" comment here

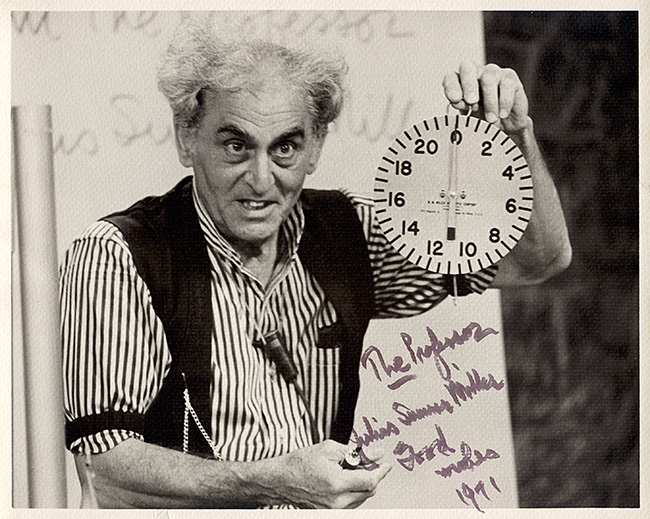

If you don't know who Professor Julius Sumner Miller is, I highly recommend

If you don't know who Professor Julius Sumner Miller is, I highly recommend  No thanks, Bender, I'm busy tonight

No thanks, Bender, I'm busy tonight

Inspired by a

Inspired by a